The Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center is one of the jewels in New York’s cultural crown. You’d think that, as a native New Yorker, I would have availed myself of this treasure by now. But I’ve never set foot in the place. I suppose that’s because my taste in music runs toward jazz, blues and country. Yet friends tell me that the sheer spectacle of grand opera is worth the price of admission, even if the singing, however brilliant, is not my thing. So the Met is on my bucket list.

When I finally get there, I’ll be prepared to take it all in. I’ve got a pair of opera glasses, a very good pair, in fact.

You don’t have to know anything about optics to know that these binoculars are of exceptional quality. Just pick them up and you’ll notice the heft. Turn the dials used to adjust the focus and you’ll feel precision mechanisms at work. Then look through the lenses and you’ll see detail and crisp definition on objects 100 feet away. These glasses are designed for high performance. They are designed to last.

The magnification, 3x13,5, is engraved on the back side, along with the logo of the manufacturer: E. Leitz, and the place they were made: Wetzlar. The country of origin, Germany, is engraved on the front, indicating a pre-World War II date of manufacture. The logo is also embossed on an accompanying Leica Eveready Case, a neat leather box that looks like a lady’s tiny handbag. A small mirror is mounted inside the cover which allowed the owner to discretely check their makeup.

Wetzlar is famous for being The City of Optics. I’ve been there, and it lives up to its moniker. A number of renowned optics companies call it home, including Satisloh. Across town is the headquarters of the famous German camera maker, Leica.

Leica is a brand name that combines the name Leitz with the word camera (Lei-ca).

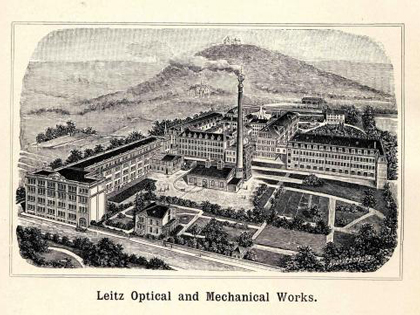

E. Leitz factory in Wetzlar, Germany.

|

According to a history published by Harvard University, the Leitz company had its origin in the Optical Institute founded

by Karl Kellner in Wetzlar in 1849. Telescopes were its main product, but were soon supplanted by microscopes. An engineer, Ernst Leitz (1843-1920) joined the company in 1865, and upon taking ownership in 1869 renamed it the Optical Institute of Ernst Leitz (Optischen Institut von Ernst Leitz).

Around the turn of the century, the Leitz company added still projectors, cinematic projectors, binoculars, and other optical equipment to their line of goods. In 1911, Oskar Barnack (1879-1936) was hired by Ernst Leitz to design an easily portable camera. In 1912, Dr. Max Berek (1886-1949) joined the company after he had finished his studies in mathematics and mineralogy in Berlin. He mathematically designed the first Leitz camera lens, a 50mm anastigmat. In 1913, Barnack invented the 35mm camera using the new lens system.

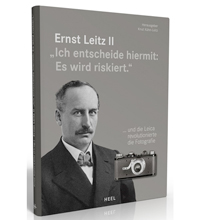

Ernst Leitz II biography cover.

|

In 1920, Ernst Leitz died, and his son, Ernst Leitz II (1870-1956) became the sole owner of the business. In 1924, Ernst Leitz II decided to put Barnack's invention into production. The new 35mm cameras were branded "Leica”.

During World War I, the German government forced the Leitz company to convert to war production. During World War II, however, Max Berek, the renown optical scientist at Leitz, refused to cooperate with the Nazi party. The German government stripped him of his professorship, but it was reinstated in 1946. During the 1930s and 1940s, Ernst Leitz II and his daughter Dr. Elsie Kuehn-Leitz, both Protestant Christians, arranged for hundreds of Jewish employees and their families to get out of Germany, thus escaping the Holocaust. Click here to learn more about Ernst Leitz II and read an interview with his grandson and biographer, Dr. Knut Kühn-Leitz.

Beginning in the 1970s, the Leitz company underwent a series of mergers and was renamed the Leica Group. Today it consists of four business units: Leica Camera, Leica Microsystems, Leica Biosystems and Leica Geosystems.

The first serial Leica (Leica 1) from 1925.

|

|

My interest in the E. Leitz company is partly professional and partly personal. The personal aspect has to do with my grandfather, Harry Hodes, the original owner of my opera glasses. Throughout his life he was fascinated by optical equipment, which he collected. He owned a Bell & Howell movie camera and projector, a Minox—the miniature camera famously used by spys—and a Fuji 35mm camera. He appreciated German engineering, which is why he drove a Mercedes-Benz and owned a pair of E. Leitz opera glasses.

My grandfather was a successful businessman, but he grew up in a poor Jewish family on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. With only an eighth-grade education, a good business sense and a lot of ambition, he got a job as a traveling salesman for a razor blade company. In the 1920s, he and a partner who was an engineer, started a company that manufactured glass ampoules for medicine. By the time he retired in the early ‘60s, he had made enough money to take my grandmother on a world cruise.

My grandfather died when I was nine. I loved him, and my memories of him are still vivid.

He left his business card in the pocket of the Leica Eveready Case, along with an import certificate from U.S. Customs. The card is so old it has no area code or zip code, just a telephone exchange, phone number and the address of his factory. When I hold my grandfather's card and look through these vintage glasses, I can see him clearly.